When building Model Context Protocol (MCP) servers, I learned two critical design patterns the hard way. What started as a straightforward implementation of a Keycloak administration server quickly became unwieldy—until I discovered Intent Multiplexing and the Command Pattern. Together, these patterns transformed a maintenance nightmare into an elegant, extensible architecture.

This post shares those lessons so you can avoid the same pitfalls.

Replicate each operation from your API and viola! you have a tool explosion. And that might not seem evident in the first place, but becomes a serious problem. An LLM might not be able to handle that large context, it might even start to halluncinate.

My first approach was intuitive or so it seemed: one tool per operation. Need to list users? Create a listUsers tool. Create a user? Add createUser. Delete? deleteUser. Simple, right?

@Tool(description = "List all users in a realm")

public String listUsers(@ToolArg(description = "The realm name") String realm) {

return userService.getUsers(realm);

}

@Tool(description = "Create a new user")

public String createUser(

@ToolArg(description = "The realm name") String realm,

@ToolArg(description = "Username") String username,

@ToolArg(description = "Email") String email,

@ToolArg(description = "First name") String firstName,

@ToolArg(description = "Last name") String lastName) {

return userService.createUser(realm, username, email, firstName, lastName);

}

@Tool(description = "Get user by ID")

public String getUserById(

@ToolArg(description = "The realm name") String realm,

@ToolArg(description = "User ID") String userId) {

return userService.getUserById(realm, userId);

}

// ... and 40+ more tools

The Keycloak Admin API has dozens of operations across users, clients, roles, groups, realms, identity providers, and authentication flows. Within a week, I had 45 separate tool methods. The problems became obvious:

LLM Context Overflow: Each tool’s metadata consumed tokens. With 45+ tools, the LLM spent significant context just understanding what was available.

Cognitive Overload: The LLM struggled to choose between similar tools.

getUservsgetUserByIdvsgetUserByUsername—which one?Inconsistent Parameters: Some tools took

realmfirst, others last. Parameter naming was inconsistent.Maintenance Hell: Adding a new operation meant adding a new method, updating documentation, and testing the new tool in isolation.

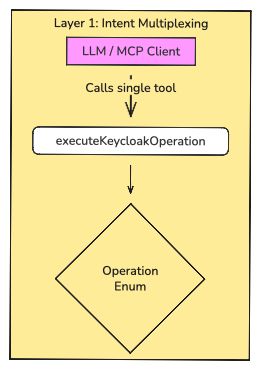

Pattern 1: Intent Multiplexing

all these tools follow the same pattern. They take parameters and execute a Keycloak operation. Why not collapse them into a single, well-described tool?

The Solution: One Tool, Many Operations

public enum KeycloakOperation {

// User Operations

GET_USERS,

GET_USER_BY_ID,

GET_USER_BY_USERNAME,

CREATE_USER,

UPDATE_USER,

DELETE_USER,

// Client Operations

GET_CLIENTS,

GET_CLIENT,

CREATE_CLIENT,

DELETE_CLIENT,

// Role Operations

GET_REALM_ROLES,

GET_CLIENT_ROLES,

CREATE_REALM_ROLE,

// ... all 45 operations as enum values

}

@Tool(description = "Execute Keycloak administration operations. " +

"Supports user, realm, client, role, group, identity provider, authentication management, and discourse search. " +

"Pass the operation type and parameters as JSON. " +

"Available operations: " +

"User ops: GET_USERS, GET_USER_BY_USERNAME, CREATE_USER, DELETE_USER, UPDATE_USER, GET_USER_BY_ID, GET_USER_GROUPS, ...")

public String executeKeycloakOperation(

@ToolArg(description = "The operation to perform (e.g., GET_USERS, CREATE_USER, GET_REALMS, etc.)")

KeycloakOperation operation,

@ToolArg(description = "JSON object containing operation parameters. Required fields vary by operation. " +

"Common fields: realm (String), username (String), userId (String), email (String), " +

"firstName (String), lastName (String), password (String), groupId (String), " +

"roleName (String), clientId (String), etc.")

String params)

Why This Works

1. Reduced Context Consumption

Instead of 45 tool definitions consuming LLM context, there’s just one. The enum values are self-documenting—GET_USER_BY_USERNAME tells the LLM exactly what it does.

2. Self-Discoverable API

The LLM can explore operations naturally:

LLM: "I'll start by listing available realms..."

executeKeycloakOperation(GET_REALMS, "{}")

LLM: "Now let me see users in the 'master' realm..."

executeKeycloakOperation(GET_USERS, {"realm": "master"})

3. Consistent Parameter Handling

All parameters flow through a single JSON object. No more remembering if realm is the first or third parameter.

4. Flexible Evolution

Adding a new operation? Add an enum value and a switch case. No new tool registration, no new method signatures.

The Trade-off

The switch statement grew large—45+ cases. While manageable, it violated the Open/Closed Principle. Every new operation required modifying this central method.

This led to the second pattern.

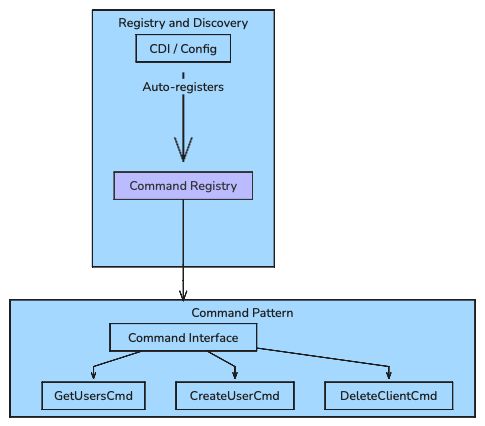

Pattern 2: Command Pattern for Extensibility

With Intent Multiplexing solving the Tool explosion problems, I still had an internal architecture issue: a monolithic switch statement that would only grow.

Enter Command pattern, probably one of the oldest design patterns in the book. The idea is to enable an extensible system by using a command based design. The Command Pattern separates each operation into its own class, making the system:

- Open for extension (add new commands without modifying existing code)

- Closed for modification (the core dispatcher doesn’t change)

- Testable (each command can be tested in isolation)

Furthermore I can now also construct a command set via the configuration. So retiring and versioning them will be easier, and above that contributors would find it easier to work with. Or thats alteast the intention at this point.

The Architecture

The Command Interface

The interface defines the basic constructs of each command. It also enforces some constructs so the design can operate in a particular flow i.e. multiplexing of the intent from the main dispatch.

public interface KeycloakCommand {

/** Which operation this command handles */

KeycloakOperation getOperation();

/** Execute the command with given parameters */

String execute(JsonNode params) throws Exception;

/** Human-readable description */

String getDescription();

/** Required parameter names for validation */

String[] getRequiredParams();

}

A Concrete Command

Here is an example of a Command. The Params are what the main dispatch looks for in the JSON. I am also using a particular service here i.e. UserService. So Commands can bring in which ever service they require to operate. and lastly the execution method where it all comes together.

@ApplicationScoped

@RegisteredCommand // CDI qualifier for auto-discovery

public class GetUsersCommand extends AbstractCommand {

@Inject

UserService userService;

@Override

public KeycloakOperation getOperation() {

return KeycloakOperation.GET_USERS;

}

@Override

public String[] getRequiredParams() {

return new String[]{"realm"};

}

@Override

public String getDescription() {

return "List all users in a realm";

}

@Override

public String execute(JsonNode params) throws Exception {

String realm = requireString(params, "realm");

return toJson(userService.getUsers(realm));

}

}

The Simplified Main Tool

And now the entire Switch and casing my way through has gone. Simplified calling based on the list of Commands that are loaded.

@ApplicationScoped

public class KeycloakTool {

@Inject

CommandRegistry registry;

@Inject

ObjectMapper mapper;

@Tool(description = "Execute Keycloak administration operations...")

public String executeKeycloakOperation(

@ToolArg(description = "The operation to perform")

KeycloakOperation operation,

@ToolArg(description = "JSON object containing operation parameters")

String params) {

// Check if operation is available

if (!registry.isAvailable(operation)) {

throw new ToolCallException(

"Operation " + operation + " is not enabled. " +

"Available: " + registry.getAvailableOperationsString()

);

}

JsonNode paramsNode = mapper.readTree(params);

KeycloakCommand command = registry.getCommand(operation);

return command.execute(paramsNode);

}

}

The 200+ line switch statement became 10 lines of delegation.

Auto-Discovery with CDI

Sure we have all the Commands, but at this point I need to have a mechanism to register all of them so the routing works from the Main tool. As in the code above registry.getCommand is the doing the trick.

The Command registry uses dependency injection to automatically find all commands:

@ApplicationScoped

@Startup

public class CommandRegistry {

@Inject

@RegisteredCommand

Instance<KeycloakCommand> discoveredCommands;

@Inject

CommandConfig config;

private final Map<KeycloakOperation, KeycloakCommand> commands = new EnumMap<>(KeycloakOperation.class);

@PostConstruct

void initialize() {

for (KeycloakCommand command : discoveredCommands) {

KeycloakOperation op = command.getOperation();

// Apply configuration filters

if (isEnabled(op)) {

commands.put(op, command);

}

}

Log.infof("Registered %d commands", commands.size());

}

}

Configuration-Driven Command Loading

Finally, some more extensibility, adding config to enable, disable commands. Deploying this in a platform like Kubernetes or OpenShift using ConfigMaps will make it even further interesting.

The Command Pattern enables runtime configuration:

# Disable dangerous commands in production

keycloak.mcp.commands.disabled=DELETE_USER,DELETE_REALM,DELETE_CLIENT

# Or explicitly enable only what's needed

keycloak.mcp.commands.enabled=GET_USERS,GET_REALMS,CREATE_USER

This would have been impossible with hardcoded switch statements!

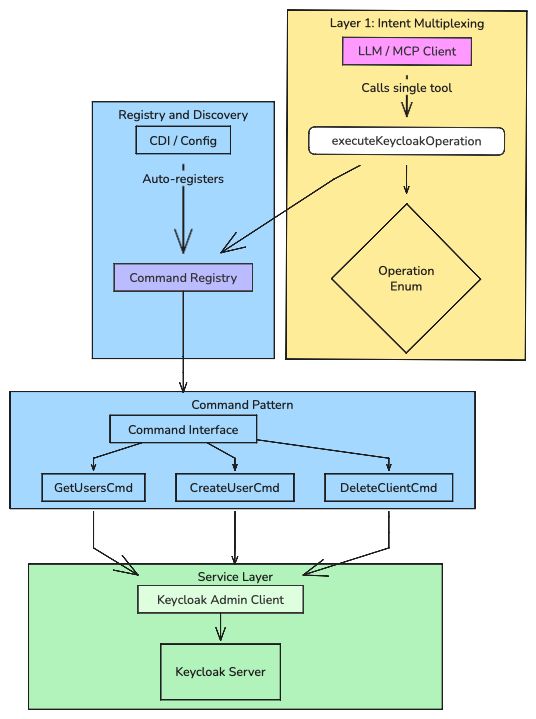

The Combined Effect

These two patterns solve different but complementary problems:

| Pattern | Problem Solved | Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Intent Multiplexing | LLM context explosion, tool discovery, parameter consistency | Clean LLM interface, single entry point |

| Command Pattern | Code maintainability, extensibility, testability | Clean developer interface, easy to extend |

Together, they create a layered architecture:

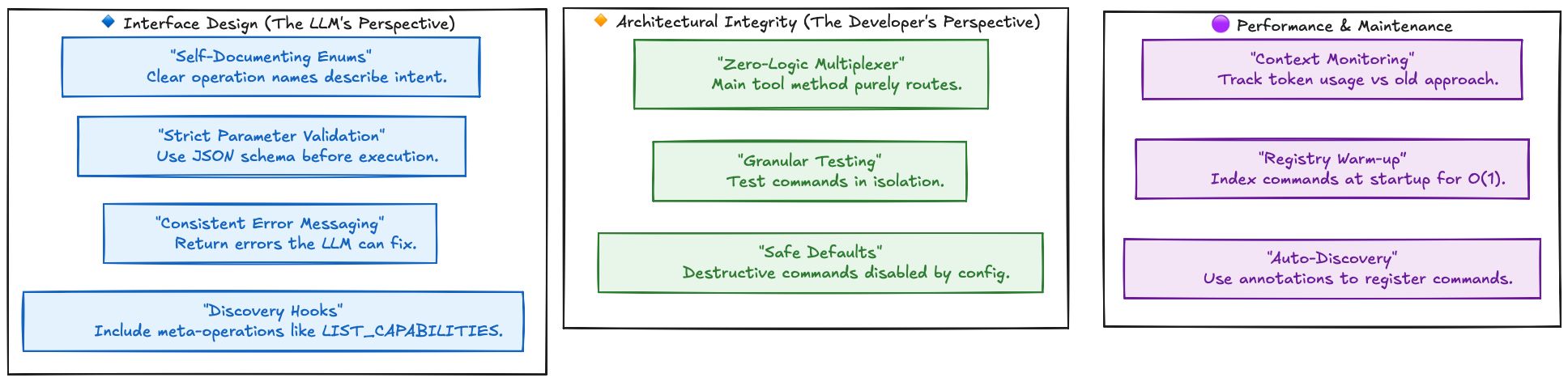

A Checklist for these patterns

To ensure your implementation of Intent Multiplexing and the Command Pattern remains robust as your project grows, you could follow this checklist during development:

Conclusion

By separating how the LLM interacts with your server from how your code executes those requests, you solve for both performance and maintainability.

Step 1: Intent Multiplexing (The AI Interface) By “multiplexing” dozens of operations into a single tool driven by a clear Enum, you minimize token consumption and provide the LLM with a structured, self-documenting workspace. This eliminates tool sprawl and reduces model “confusion” during tool selection.

Step 2: The Command Pattern (The Developer Interface) Internally, the Command Pattern keeps your codebase modular. By using auto-discovery (CDI) and individual command classes, you can extend the server’s capabilities or toggle features via configuration without ever touching the core dispatcher logic.

I am sure there is more design patterns out there. These two gave me more clarity and simplicity to work with.

The full implementation is available in the Keycloak MCP Server repository. Contributions welcome!